On a bronze plaque at the foot of the Statue of Liberty visitors read Emma Lazarus’s 1883 poem the “New Colossus” with its oft quoted lines, “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.” Contrary to these well intentioned images, our immigrant ancestors -Nonno and Nonna to us older generation- were far from being the “refuse” of Europe. In fact, very often they arrived here as skilled people. In the old country, they had been stone masons, seamstresses, tailors, farmhands, carpenters, fishermen, farmers, and shepherds. As the grandson of an Italian shepherd, I would like to share some background about this venerable way of life and its relationship to immigration. For centuries, raising and moving sheep over long distances in Italy created tremendous wealth and offered an income for many families. This was especially true in nowadays Abruzzo and Molise. With such a storied past and with so many former Italian shepherds among the arrivals at US ports of entry, let’s take a close look at la pastorizia, Italian for sheepherding.

Sheep Raising, an age-old Italian Tradition

Ancient peoples in Italy began raising sheep before anyone started keeping records. During the Roman Republic, Empire accounts show that shepherds moved their flocks from higher, colder regions to warmer, lower pastures over considerable distances. In Italian, this seasonal movement of animals is known as la transumanza. Since in ancient times most clothing was made of wool, the sheep economy was an extremely important commercial venture. With the dissolution of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD, security broke down in Italy. Open fields and tratturi, sheep runs, where the animals had once peacefully traveled were no longer safe from highwaymen and roaming armies. In fact, moving sheep long distances became impossible.

It was only in the 12th century that the transumanza began again. The Norman kings, conquerors of Southern Italy and Sicily, created a realm that united Abruzzo and Molise with the vast green plain of the Tavoliere della Puglia, close to the Adriatic Sea, an ideal area for pasturing sheep during the winter. Most importantly, they enacted a body of laws granting Abruzzese and Molisano shepherds many rights, including the free movement of flocks through fields and towns. A network of two thousand miles of tratturi made this possible; long distance sheepherding was reborn. Not surprisingly, the Norman monarchy enriched its treasury imposing taxes on the flocks and rents on the winter grounds in the Tavoliere.

The later conquerors of Southern Italy, the Swabians from present day Germany and then the Aragonese of Spain, continued and refined protections for sheep raising. Thus a vast network of privileges and regulations brought into being a pastoral civilization involving thousands of families from dozens of shepherd towns from L’Aquila all the way to sunny Foggia in Puglia, near the Adriatic Sea. Imagine the commerce created by this economic dynamo as the need for horses, sheepdogs, leather goods, cheese making equipment, tents, and tools for shearing wool infused the economy. In the fall of 1604, nearly six million head of sheep arrived in the South. This was sheep raising on an industrial scale.

A Shepherd’s Life

Try to picture my grandfather Giangregorio’s shepherd life, if you will. The migration begins in late September, in the high country of his Capracotta in Molise. At the chapel of the Madonna of Loreto, just outside town, the shepherds pray for protection of the families they leave behind and for a successful transumanza. Then men, sheepdogs, flocks, mules, and horses move ever southward over the unpaved sheep runs. At times they ford dangerous rivers, the weaker animals carried on their shoulders. They overnight in tents, sometimes in a welcoming barn, or even in rural churches. While still in the high country there’s always the danger of wolves carrying away sheep. Once in Puglia, the shepherds’ work turns to daily milking, cheese making, and readying the flocks for shearing. In May, they lead the flocks home, this time with new lambs. Just before entering Capracotta’s gates, Grandfather and his companions make a final, essential stop. On their knees, they again offer prayers at the Madonna’s shrine, this time in reverent thanksgiving.

In villages and towns emptied of men, the women carry on. They produce clothing and tend garden plots. They gather on wintry evenings to share news and stories by the fireplace while embroidering linens to fill a girl’s corredo, dowry. The men left enough chopped wood, but it’s the women who will keep the home fires burning through the long mountain winter. May will be a time of reunion and feasting.

Farming overtakes Shepherding

By the mid-1800s, the generation before Italians began leaving for the Americas, the once dominant sheep economy began to decline. Plants from the New World, such as corn and new varieties of legumes, introduced more cash crops. The revolution in farming technology with its steam-powered tractors and harvesters made farmland much more productive, more lucrative. With its marshes drained, the verdant plain in Puglia became divided into large agricultural estates that did not welcome hordes of sheep on its lands. Left with declining opportunities, shepherds tried farming near their hometowns.

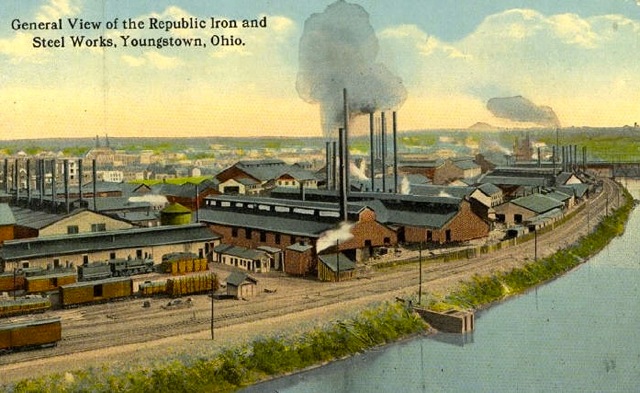

From Shepherds to Ohio Steelworkers

Who knows if my grandfather Giangregorio and his paesani, former Capracotta sheepherders in the High Molise, had any idea that they would one day spend the rest of their working lives in Ohio’s steel plants and iron foundries? Did handbills in their hometown lure them to the Midwest’s booming industrial belt? Did the difficulty of turning from shepherding to farming in nearly mile-high Capracotta force the question? Too cold there to grow wine grapes or olives. The 1880s European farm crisis hit Italy hard with declining prices for wheat. Truth be told, many faced a grim future at home as sharecroppers.

Around 1900, new technologies revolutionized US iron and steel production. This was especially the case in the industrial region stretching from Pittsburgh through the Ohio and Mahoning Valleys. Older methods of producing these metals in small batches gave way to new ones with gigantic open hearths or ovens that required thousands of men each shift. The need for strong backs in Ohio’s metal industries somehow was communicated to the towns and villages where former shepherds were struggling to eke out a living from increasingly overworked fields. Giangregorio and thousands like him responded. They left the declining sheep industry and the hard luck farms of their native villages to become the steelworkers of a booming new economy in the US. Perhaps for these men, used to long separation from family, leaving home for Ohio’s mill towns was not quite as traumatic as for other Italians of this period.

So dig deep when researching your family’s history. Your steelworker ancestor may have spent his youth leading white flocks through cool mountain valleys to the lush Tavoliere della Puglia. If true, know that he practiced one of Italy’s most important and ancient trades before he began turning out steel “Made in the USA”.

Ben Lariccia